Last Days of Mongolia

This was it. The last night camping in the freezing cold, last night photos of the Gobi Desert, last pot of buckwheat cooked on my camping stove.

Last cuddle under two puffy sleeping bags. Last morning sunlight through the thin tent walls. Last warmth, last hot cup of coffee.

Patrick Watson played on my little speaker for the last time as the sunrays warmed my face. Last kiss in the morning sunlight.

I listened to the wind and the piano, thought about where I was… somewhere in the Gobi Desert, and I felt like my life was just a fantasy, or a novel. But it was so real.

You see, it’s not just Mongolia. I’ve been living like this for almost 12 years, sometimes more intense, sometimes less, sometimes stopping to play the job game or to write a blog, sometimes backpacking for months, or years, living on a boat, in a car, a hammock, wherever. I wrote out the details of this past month just to give you an example of how you can travel with little money, but the best part of the experience is something that I could never describe or explain in words or pictures.

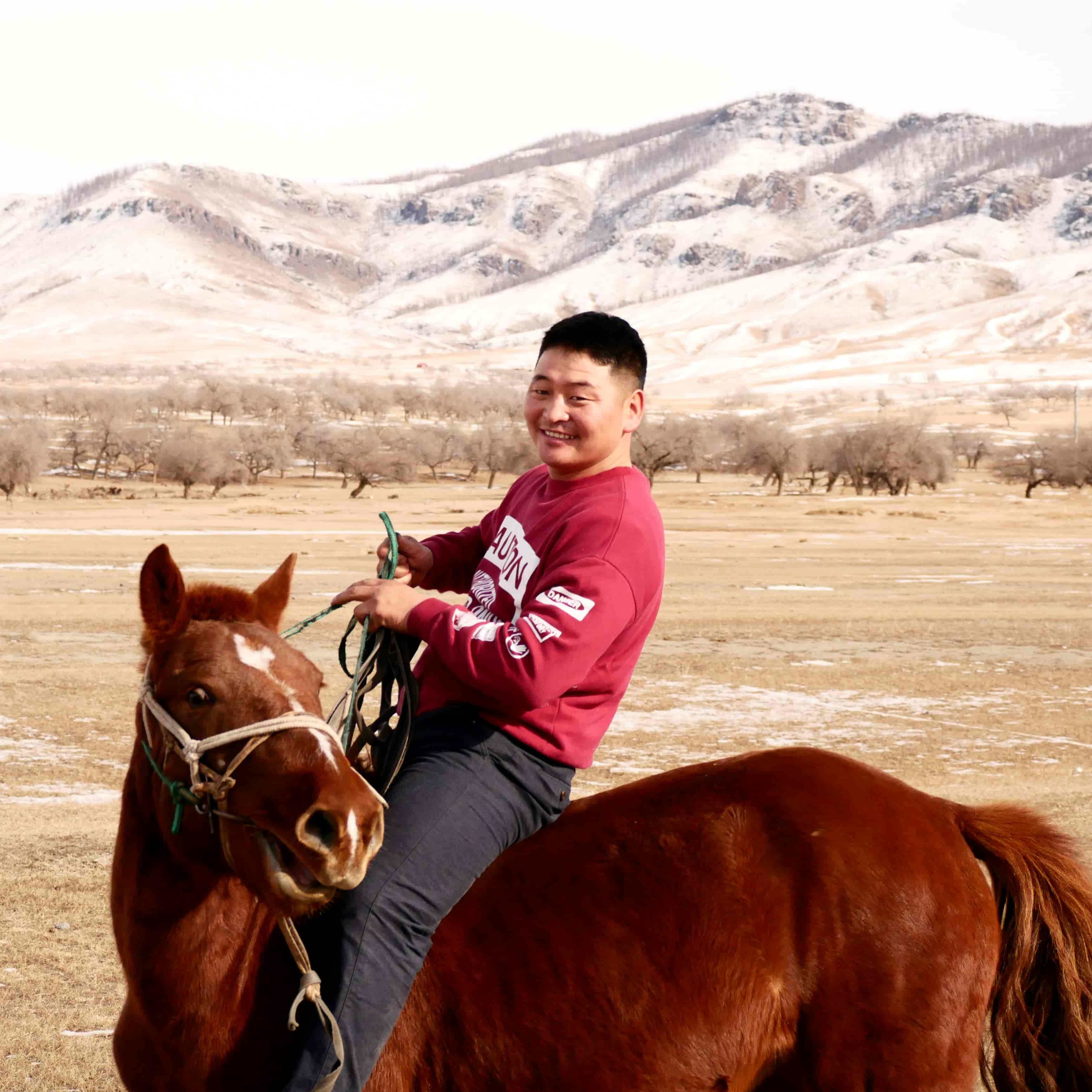

I looked back at this last adventure- meeting Felix, hitching from Russia to Ulaanbaatar, hitching to Lake Khuvsgul, getting invited to yurts, homes and apartments; adopting a kid and a dog for a night, camping in a snowstorm. Being taken into a family, riding a horse and a motorcycle, climbing a sacred mountain, sleeping in a family yurt. The dead sheep van, the overnight train, camping in Ulaanbaatar; hitching a ride to and from Gorkhi Terelj National Park, camping in the boulders, feeding camels, meeting friends. Hitching to the Gobi, camping in the Khongor Sand Dunes; the wind, the cold, the sand, the stars, the sunrise on the frozen lake. Seeing ice fields in the Yolin Am Canyon, Mukhar Shivert and White Stupa. All of this for roughly $300 :).

But you could never buy such an adventure because the best and most important part of it is priceless- it was Felix, it was Uncle, Buddy, Thunder, Javkhlan, Gorkhi Terelj driver friend, and everyone else whose name we can’t pronounce or remember :). It was every smile and every laugh, every deep conversation we had, every wordless act of kindness from a stranger. Every trade-free interaction made on a true human to human level, that made us not just think, but truly feel and understand that we are all one human family. That’s what money can never buy.

We packed up our tent for the last time, walked back onto the road by 2pm, and hitched a lift to Mandalgovi. We were picked up by a poor family with a 4-year-old girl. We gave her some stickers and she was so happy :).

We caught three more lifts, ran out of gas in the last ride but pushed the car to a petrol station and made it to Ulaanbaatar by 10pm. We took a local bus ($0.20) to a hostel ($8) and spent the night there. In the morning, I took off to the Dragon Bus Station. I took a bus from Ulaanbaatar to Altanbulag ($6.30), which is the town at the main border of Mongolia and Russia. I got out of the bus, walked to the border and then asked someone to give me a lift to Russia. You cannot cross the border by foot, so it is a standard procedure that drivers ask for money to bring people across. I paid 100 rubles (about $1.50).

I had no idea where I would sleep that night and this time I was alone, it was about -25°C outside, and it was dark by the time we crossed the border. Lucky for me, there were three ladies in this vehicle and one of them offered me accommodation just across the border for 150 rubles (less than $3). The accommodation was the floor of a grandma and grandpa’s old soviet apartment, but it was warm and they even gave me some sweet milk tea and a homemade pastry.

I slept well and left their apartment early in the morning; walked to a café, had breakfast ($2.50), then walked to the main highway to hitch a lift towards Irkutsk (560km away).

I walked down the road for almost two hours before someone stopped. A small truck pulled over and a nice little man gave me a lift all the way to the outskirts of Irkutsk. From there, I found a local bus to the city center and then walked to the apartment I was renting. I paid rent the next day and told the landlord that I’ll move out in one month.

Then I finished the climate change book, finished this blog, and told my friends I was leaving.

A wave of emotions ran through me, a bit of sadness. I sat and thought for a while.

It was something about the cold.

-35° in Irkutsk. About the same in Ulaanbaatar. Plus wind. Interesting fact, Fahrenheit and Celsius meet at -40°.

I thought about our winter camping experience. I got to feel the cold. The real, down-to-the-bone cold, the kind you can’t escape when all you have for shelter is a tent. It was harsh sometimes. But for me, it was all just play pretend. Sleep in a tent when it’s -20°, sure, but I have 3 warm jackets, 2 sleeping bags and a cute Canadian guy to keep me warm :). Too cold? Pay $4 to sleep in a yurt, no problem, then go back to your warm apartment.

But some people can’t pay $4 because they don’t have $4. I saw many homeless people in Ulaanbaatar and Irkutsk, searching for food in frozen trash bins, sleeping on the street, begging for money, in a place where it gets down to -40 degrees. I think it’s hard to understand how cold that is unless you feel it for yourself. And it’s hard to imagine what living in real poverty is like, but poverty in the world’s coldest cities is on a whole other level.

Ulaanbaatar hosts almost half of Mongolia’s population, about 20% of which has arrived in the last 3 decades. Many people have immigrated to Ulaanbaatar after natural disasters, like cold spells called dzud, wiped out their herd animals and destroyed their nomadic lifestyle. These cold spells kill millions of herd animals and have been getting more frequent in recent years. Once such a disaster occurs, the people have little choice but to pick up their yurt and move to Ulaanbaatar in search for work [Source].

Imagine growing up as a simple sheep herder, then having your herd and your lifestyle destroyed, being forced to move to an overcrowded, extremely polluted city ghetto, not being able to cope, or to find a job. You’re destroyed psychologically. There’s no social support, no help from the city dwellers. One day you find a bottle of vodka or some petrol to sniff. Escape, feel warmth, feel better. Next thing you know, you’re out on the street. No pity, no warmth, no food in the trash.

Next time you see such a person, remember that it could have been you. Had you been born in the wrong country, to the wrong family, had you stumbled upon the wrong situation.

Had you just been that unlucky.